An episode in the last hundred years of American democracy

Originally published in The Polis on Medium.com on February 21, 2024

The time is 1917 and the United States formally entered the First World War, which set the stage for the rise of Hitler, the Second World War, the Holocaust, and the European Union. It also marked the start of the Bolshevik Revolution which set the stage for the Soviet Union, the cold war, the fall of the Soviet Union, and the rise of Putin. And in 1917 Britain signed the Balfour Declaration which set the stage for the creation of Israel and the Palestinian question and the current Gazan war. It was a momentous year whose events we’re still reeling from a hundred years later. It was coincidentally also the year John Fitzgerald Kennedy was born.

Less momentously, Charles Scruggs in his book The Sage of Harlem, wrote that “In 1917 Mencken woke up and discovered himself to be a Negro.” Scruggs, an historian focused widely on Black American literary history, was referring to the influence H. L. Mencken had on promoting the work and careers of Black authors of the Harlem Renaissance.

Mencken was a second generation German American and the influential editor of the American Mercury, the leading literary journal of the 1920’s. Mencken endured unhappily the steady erosion of German cultural influence in the States during and following World War I and it’s fair to say took it out on America, naming names and dishing dirt far and wide. Yet, in the course of pointing out America’s warts, he also showed his sympathy for the underdogs, especially Negroes.

Scruggs writes, “During the war and post-war years, Mencken discovered black intellectuals, and they discovered him. Mencken stepped up his aggressive counterattack against white America and white Americans. White people no longer looked so superior to him.” Scruggs implies that Mencken was bitter about the loss of prestige of Germany and Germans, and held white society responsible. Actually, he held democracy responsible.

Mencken always had a low regard for the “booboisie,” especially the “white trash” of the American south. The term “white trash” has a long history in early America and was used by both Blacks and whites to describe uneducated and poor whites, particularly in the south. Mencken used it freely. But “booboisie,” a Mencken concoction riffing on the French “bourgeoisie,” lampooned the hypocrisy he detected in the words and attitudes of those who, without merit, saw themselves as betters.

In fact it was also in 1917 that Mencken wrote an editorial piece for the New York Evening Mail called the “Sahara of the Bozart.” Bozart was another linguistic riff based on the French “beaux arts,” the classically inspired art and architectural style of the late 19th century. It was another slap at southern pretensions to being a refined society. Mencken speculated that “the civil war actually finished off nearly all the civilized folk in the South and thus left the country to the poor white trash, whose descendants now run it.”

Mencken didn’t like prohibitionists, evangelicals, and racial bigots, all of which he found under every rock in the south. From his diary, published long after his death, it was clear that he didn’t have any higher regard for the lower echelons of Black American than he had for those of white America. He was a full-fledged elitist.

Still because he was an editor of a journal valuing social innovation and artistic creativity, he admired the talents and achievements of Black individuals. Scruggs includes an admiring quote from the Black owned Pittsburgh Courier:

[Mencken] points out what every well-informed Negro knows: that almost everything that is internationally recognized as American is derived from the dark brother. The list includes music, cooking, consumption of gin, language, the cabaret rage, dancing and religious practices. With great gusto Mr. Mencken portrays the manner in which the lowly Negro has forced his culture upon the none-too-reluctant Caucasians, and makes some highly interesting and entertaining comments thereon.

In the “Sahara of the Bozart,” Mencken mocked the southern Christian attitude, whereby “the acts of man are estimated chiefly by their capacity for saving him from hell,” and bemoaned the “orgy of puritanism that goes on in the south, [abetted by] an orgy of repressive legislation. …a conspiracy against his effort to let some joy into his life.”

It’s now more than a hundred years since that withering characterization of southern values shocked the south, so it’s somewhere between depressing and frightening that you can still see so much evidence of it today. It’s true and sad that we are still witnessing “orgies of repressive legislation” in southern states, racial animus, and over zealous finger-wagging Christians eager to condemn. A hundred years!

Mencken evidently liked to claim that his mocking contributed to sparking the Southern Renascence that produced William Faulkner (b. 1897), Eudora Welty (b. 1909), Tennessee Williams (b. 1911), and Carson McCullers (b. 1917), among others.

Critics who look at these acclaimed writers of the 1920s to 1040s find that the themes they explored were drawn from the same cultural low points that Mencken disparaged. If so, then it was these writers being honest about who they were that turned their writing into art. They raised the skirts on the south’s pretentiousness and exposed its dirty knickers. But at the same time, these writers were proudly southern, in spite of how many of them were personally wounded. And wounded they were, by depression, drug and alcohol addiction and especially loneliness.

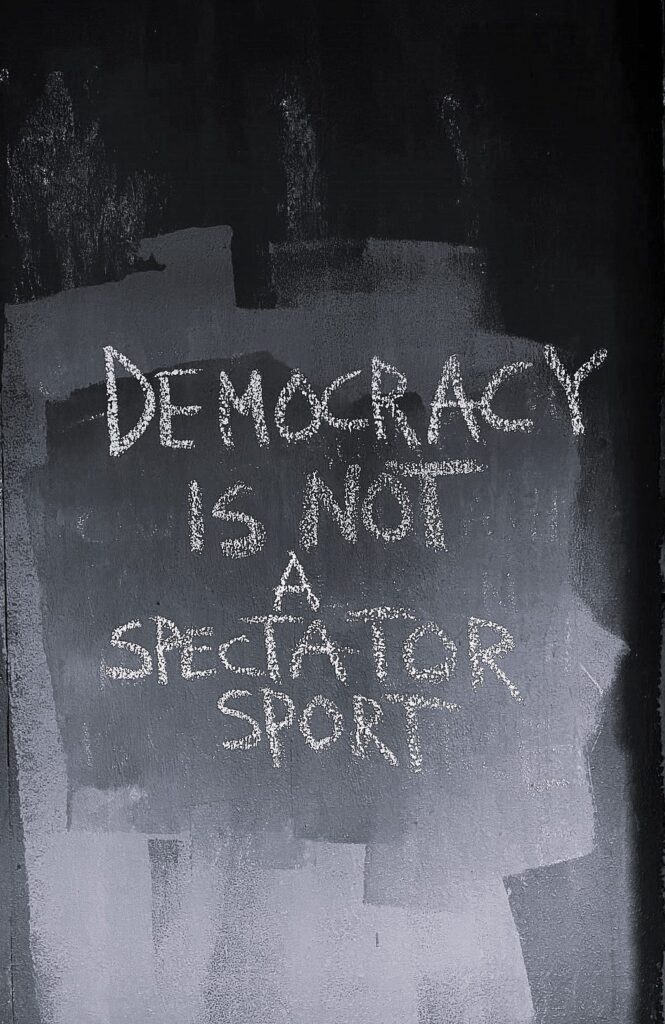

So Mencken had it right about the south, but he largely laid the blame for its human failings at the foot of democracy. And here is where the story gets more interesting and where Mencken in his book Notes on Democracy raised questions still relevant today.

Is the south the way it is because democracy is too permissive? Would the south have turned out better if the Founders hadn’t concocted a system that catered to good and bad actors both, giving them equal access to power? Did the “all men are created equal” falsehood as Mencken saw it determine that a hundred years wouldn’t be long enough to solve social problems? All hard questions.

The way to address these questions, of course, is to stress the sunnier side of democracy and contrast it with its alternatives, of which there are many examples: the Roman Empire, Tsarist Russia, Maoist China, Hitler’s Germany, Putin’s Russia. All these examples entrust individuals and societies to the whims of a single person. However enlightened that single person may have presented himself (always a “him”) in order to claim power, he always seems to eventually tightly pull back the reins on dissenters. At least democracy, in principle, keeps the dialog flowing. It may be a clown car, but it’s not likely that any one clown will become the Batman Joker. Hold that thought!

Mencken seemed to at least appreciate the sport of democratic politics. He said of would-be despots: “the pain of seeing them go up is balanced and obliterated by the joy of seeing them come down.” Democracy. Good guys, bad guys, drama, intrigue. Made for Hollywood.