Note: This article was published in the Spirit of Jefferson on February 23, 2023.

There’s knowing about history and then there’s living with history. That distinction shows itself between those who study history through documents, books, photos and oral recordings, and those who want to recreate in their lives the tastes of the people who lived 50 to a 100 or more years ago. Naturally, the same person can do both.

These are the people who for whatever reason have become fascinated by the stuff and styles of the past, the big stuff like buildings and the small stuff like antiques. Their fascination can extend even to keeping alive the crafts that created the artifacts they value and recreating or reenacting the practices of old. This is often an important objective of historical parks, most notably and closest to home, the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park.

At Harpers Ferry objects that have outlived their usefulness for the general population of today come to life in the historical setting of the town itself. So we get to witness the costumes, the workplaces, the instruments and the work routines of our neighbors who lived there in the mid 1800s. In any particular year hundreds of thousands of visitors come to experience and enjoy the history the park recreates for them.

As to the material objects you’ll see in Harpers Ferry, you won’t find them for sale at Walmarts. Even when you do find some object that resembles a museum piece, a reproduction often, you just need to peel back the surface to find that the makers of these newly made things have taken a lot of shortcuts in workmanship and materials. They will typically be machine-made, rather than hand-made, and will often make shortcuts with the character and quality of materials. They’re not authentic and to collectors, authenticity is important.

Many of the most valuable antiques ultimately make their way into museums, including the three major county museums: the Jefferson County Museum in Charles Town, the Shepherdstown Museum and, of course, the Harpers Ferry National Park collections.

Thanks to the urging of Eleanor Finn, I was able to get a one-on-one tour with her of the Shepherdstown Museum. It is the smallest of the three, but housed in the historic Entler Hotel, it sits in its own authentic context. Finn is a former president of the Shepherdstown Historic Commission and now organizes the docent pool for the museum. Her efforts have been important in setting the direction for the museum, especially pertaining to surviving artifacts of the town’s African American communities.

Collecting bits and pieces of history is done at a scale much less technical and exacting than taking a whole down-and-out building and making it habitable again. The impetus for getting involved with a project of this size, which can last years and can cost thousands of dollars, has to do with building a “sense of continuity, memory, belonging and identity.” These are the words of Thompson Mayes in his book “Why old places matter.” Mayes, who is an executive with the National Trust for Historic Preservation and a Shepherdstown resident along with his husband, artist Rod Glover, argues that even though these motivations are subjective, they are economically fruitful.

Preservation projects will typically cost thousands of dollars and those costs have to be justified by calculating a return on investment. Fortunately, in many communities around the country, and certainly in Jefferson County, the return on investment involved in restoring historical homes is usually positive. Renovation hikes the real estate value of a property along with contributing to building and sustaining a tourist industry.

Shepherdstown and Harpers Ferry, for example, have become favored tourist destinations because of the significant investment both communities have put into caring for their buildings.

In Harpers Ferry, this was sparked to a large extent by the federal government declaring the town a historic national park. In Shepherdstown it was largely private initiatives undertaken by newcomers with means and enthusiasm who renovated properties one-by-one. Shepherdstown provides guidance in these restorations through the town’s Historic Landmarks Commission, which has codified a set of architectural standards intended to maintain the architectural history of the town. At the same time it allows for upgrades in facilities to make the homes meet current-day building codes.

Both towns now have well regarded and stable tourism based economies as a result. They both are also relatively more gentrified and expensive for longtime residents than other towns in the county, and that’s another less welcome consequence.

In an interview with Mayes, we talked about the impacts of historic preservation and the effects it can have on gentrification and displacement of residents. He acknowledged that it’s important to be alert to these possibilities and to take measures to prevent it. When a community sheds its residents and its architectural past, it puts the identity and collective memory of the community in jeopardy.

Preservation, Mayes said, “is part of a living society and the society should be welcoming of it.” A community has to be just as livable, maybe even more so, when the preservation work is completed, as when it was before it started. If it was diverse and welcoming to begin with, as Shepherdstown was, it should be that way at the end too. Preservation should contribute to the continuity of a community, not disrupt it.

Two friends of mine, John Restaino and Mark Schiavone, have for more than 35 years lived in the world of architectural preservation. It’s been an anchor of their relationship, with each complementing the other in the critical skills needed to revitalize old homes: woodworking, plumbing, stonework, electrical work, plastering, even flood control. Each of these skills came into play on the first of three projects they tackled together. It all started with an 18th century, three-story stone house in Gerrardstown in Berkeley County.

Restaino was newly arrived from history-heavy upstate New York where he had settled down after a year in the forests of British Columbia. He built and lived in an impressive log home using techniques he’d learned in Canada, but it was stone and stone houses that really held his interest.

A visit to friends here in West Virginia (me being one) in 1982 exposed him to the Gerrardstown house, which was lying idle and unlived in at the time. It took a year, but after selling his home in New York, he purchased the Tanyard House, as it was known locally, for about $20,000. He began immediately with the work, which was to take most of the next 10 years. Schiavone came onto the scene about halfway through. They lived in the house as they were revitalizing it.

At the end of this period they took on the paperwork job of applying to the National Register of Historic Places to designate Gerrardstown as a National Historic District. They had the cooperation of two close neighbors who were also doing preservation work on their homes: Tom and Beth Gleason and Georgiana Pardo. The work of researching the more than 100 historic properties of the town instilled pride of residents in the town and its history, and they showed that pride in a centennial celebration in 1987. The application itself was approved in 1991.

It’s hard to know what kind of impact the recognition of Gerrardstown has made on the residents of the town since 1987. Not much has outwardly changed in the community. It still has much the same feel as it did 35 years ago; that is, it hasn’t really blossomed into a tourist destination, but many of the residents of that time or their families are still there.

Restaino feels good about that part, but since he and Schiavone, Pardo and the Gleasons have moved away, some of the energy has gone out too. Restaino believes that one reason has to do with the traffic density on W.Va. Route 51, which runs through the middle of town and likely inhibits enthusiasm for further restoration work.

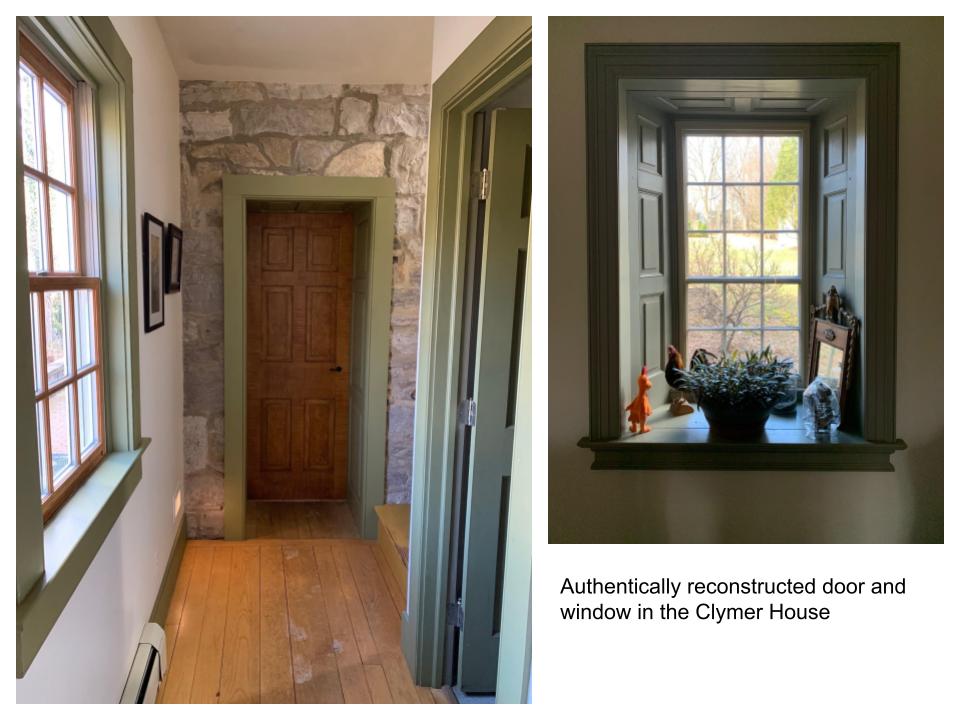

The work in preserving the Tanyard House was painstakingly detailed. It involved leveling the earthen ground floor with its walk-in hearth (the traditional kitchen “appliance” and heat source) and laying down what would be an authentic wood floor of the period. The stone needed repointing, the roof replaced, the circular staircase repaired, the nearby creek channeled to prevent flooding, and on and on. With the heavy work essentially done, they acquired a second house in town and began restoring and renovating it. That was another three years, after which an opportunity to live in the country, in Jefferson County, presented itself in 1997.. This was another vacant 18th-century stone manor house on an old estate outside Bakerton, then and now known as the Isaac Clymer House.

Restaino and Schiavone have now been at the restoration work on their home for 24 years. It’s nearly done (maybe!), but it is beautiful as it stands now and they’re in the process of preparing the paperwork to file for a National Register designation.

Restaino and Schiavone estimate that about 50 percent of the furnishing and art work that they have in the house are antiques or faithful reproductions, several of which Restaino has meticulously crafted himself.

I asked them about their persistence in getting all the historical details and the craftsmanship right. Besides simply liking to live with the past as a romantic or esthetic choice. Restaino said that his eye is on the future as he does his work and collecting. He feels, as Mayes does, that restoration is really the goal of preservation and conservation. (Another aspect of their focus on the future is that they have deeded a preservation easement to the Jefferson County Farmland Protection Board, ensuring the majority of their 50-acre property will never be developed. Not coincidentally, Schiavone is the director of the Berkeley County Farmland Protection Board.)

Restoration makes a home livable in the present, but, just as important, Restaino says, “it also gives the house another 100 years of livability” – obviously for someone else’s benefit. The saddest thing Restaino sees in derelict houses, those that can’t be made livable, is the loss of opportunity for the community to know and benefit from what their builders created. It’s a loss of a community’s continuity with its past, leading ultimately to an erosion of its identity.

Similar Posts:

- None Found