Note: This article was originally published in the Spirit of Jefferson on October 15, 2022.

People sometimes do wrong by other people, and it’s the role of our law enforcement system to detect those wrongs, and it’s the role of our judicial system to redress them. Sometimes the police as the discoverers and interpreters of evidence of wrongdoing get the facts right, and sometimes they do not.

Our justice system, of course, operates on the principle that someone is innocent until proven guilty, and we leave it up to judges and juries to weigh evidence and testimony under the rules governing a fair trial before determining guilt or innocence. It is not the job of the police and especially not random members of the community or the press to pass judgment.

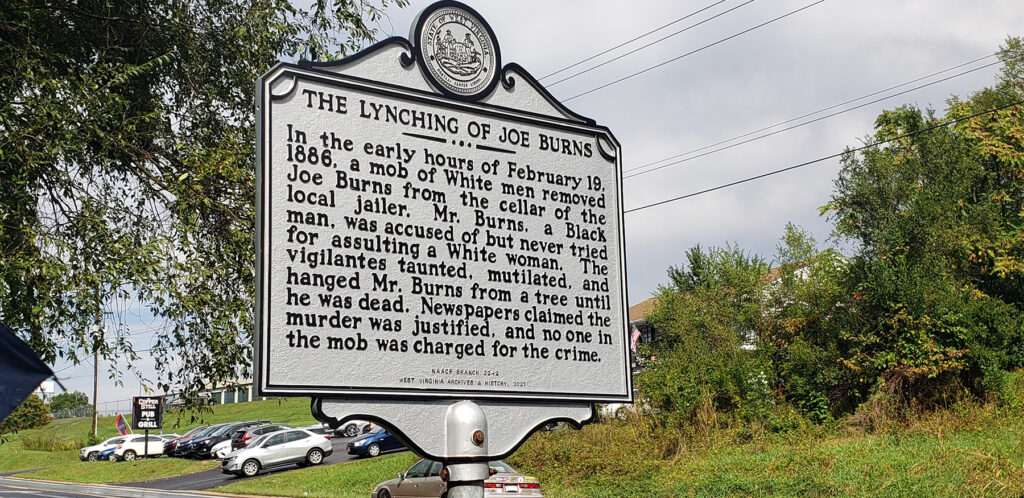

This is a story of when that judicial process was denied a man named Joe Burns. It’s a story of what the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit organization based in Montgomery, Alabama, calls “racial terror lynchings”— that is, hangings of black people that “generally took place in communities where there was a functioning criminal justice system that was deemed too good for African Americans.” Equal Justice, which provides legal representation to prisoners who may have been wrongly convicted of crimes, has documented some 6,500 such American lynchings, the overwhelming majority in the South between 1865, the end of the Civil War, and 1950.

The practice of lynching in the Eastern Panhandle is not widely attested in newspaper accounts, but on Feb.19, 1886, it did happen to a young black man named Joe Burns. Burns was accused of rape and robbery by a young, white woman 12 days earlier on Feb. 7. That day was a snowy Sunday afternoon when the alleged victim was reported to have been accosted as she was walking along the railroad tracks leading away from the Martinsburg railroad station. She had just arrived from Baltimore and was walking to her parents’ home.

The details of the alleged rape and robbery were reported in the Martinsburg Independent on Feb. 13 under the title “A Devilish Deed: A Fiend Outrages a White Girl in Broad Daylight.”

The police arrested and charged Joe Burns based on the testimony of the young woman and he was jailed to await trial. How he came to be apprehended is not known, but the Independent’s article reported he had implicated himself. He allegedly told an acquaintance that, “I expect to have a big row about a white girl.”

What is unreported and unknown is whether there was any medical exam to confirm a rape; whether Burns was found with any evidence of the alleged robbery; whether the victim mistakenly identified Burns or whether she knew Burns previously, since their families likely lived close to one another; and whether the alleged victim encouraged any of Burns’s attention.

It’s been substantially documented that black men were socially prohibited in the South from “interacting socially” with white women, and many lynchings took place because of such accusations. The testimony of white women would often be taken at their word and not questioned, even in courts of law. The title of the Independent’s article reporting the alleged crime is itself evidence of this practice.

When Emmett Till, a 14-year-old black teenager from Chicago, made the mistake of whistling at a white woman in Money, Mississippi. He was accused by the women of attempting to molest her and from that “social indiscretion” the incident escalated into a crime for which he was kidnapped, tortured and lynched. This happened in 1955, but it wasn’t until 2017 that The New York Times reported (Feb. 27, 2017) what happened. The woman involved admitted her “long-ago allegations that Emmett grabbed her and was menacing and sexually crude toward her” were not true.

For something that didn’t happen, Emmett Till was brutally murdered.

Is it possible, speaking as the defense attorney that Joe Burns never had, that something similar took place on the railroad tracks in Martinsburg? We don’t know and can’t ever know because Burns did not receive a fair trial. He didn’t receive any trial.

Instead, a group of white men on the night of Feb. 18, likely inflamed by the Independent’s biased coverage of the matter, dragged Burns from the cellar of the jailor’s home. He had been moved there from the jail based on information that a mob would be attacking the jail. They found him in spite of the jailor’s precaution and took him several miles away to a location south of Martinsburg near Darkesville and hanged him from a tree.

In fact, the only parties who we know were definitely guilty of a crime were the members of the mob that lynched Joe Burns, for which the papers of the day pronounced them misguided at best.

Even this paper, The Spirit of Jefferson, in commentary reporting about the lynching (Feb 23, 1886), had the following to say: “We are not going to defend Joseph Burns. He committed one of the most atrocious, infamous crimes that could be committed in a civilized land. He was a brute, if ever there was one, and he richly deserved to be hanged. But it would have been far better to have let the court act and heard its decision first. The law can never be respected or given full dominion over the acts of a nation, state or county so long as it is set at naught and its provisions robbed of their force and execution.”

Today’s Spirit would have printed the accusation, as a matter of conjecture, not fact, and reported the final sentences as its considered opinion.

On Sept. 25, Joe Burns’ descendants and others gathered to unveil a memorial at the probable site of his hanging in front of the Purple Iris mansion on Winchester Avenue. The research and memorial resulted from a project named the Eastern Panhandle Community Remembrance Project.

Additional details about Burns and his lynching and about the makeup and work of the Remembrance Project can be read at berkeleycountywvnaacp.com/single-project.

Similar Posts:

- None Found