This article appeared in the Spirit of Jefferson on June 21, 2023.

by the American Library Association

“Literacy is our most important civil right,” she said. “Banning is counter to a free and open society.”

The culture wars rolling through our conservative states, in which I include West Virginia, have taken aim at books children read or are read to in schools and libraries. These would be books that are labeled by the soldiers in the wars as “woke,” a term that those who use it often don’t know how to define it.

Books are challenged overwhelmingly for two reasons: They’re regarded as sexually explicit, or they include offensive language. Of course, the devil is in the details. What do those people challenging books mean by sexually explicit and by offensive language? Who are these soldiers in the culture war anyway?

As you’d expect, they’re predominantly parents, but their ammunition and marching orders are often supplied to them by conservative politicians. Florida, for instance, has seriously stoked conservative parents with its Parental Rights in Education law, which projects serious doubts on the judgment of publishers, librarians and teachers to make decisions about suitable materials for children.

And is it really being too cynical to think that a politician has a political motive for wanting certain books censored and banned? Those of us who haven’t fallen off the turnip truck think yes, they do, and it’s pretty remote from advocating a “healthy” reading list for every kid. And that’s where the message of this article is aimed.

Challenging a book with the intent of having that book removed from all potential readers makes a judgment call that denies the book has any worth, at least for its target audience. And that’s not a fair judgment to make for one person to make for another, or one parent to make for another.

Before a book gets to a school or public library, it has already passed through a usually long and detailed inspection as to its worth for some audience. Publishers, who receive thousands of manuscripts every year, are the first people to render a verdict. Their judgments about worth are based on an assessment of how well a book will sell to the target audience the author has written it for. If they publish a book intended for an elementary school audience, they have already judged it to be absent sexual content or offensive language. And they’re predicting that it will sell.

Can they be wrong? Sure, it happens.

But then the book will typically be reviewed objectively by outside organizations and individuals. These reviewers focus primarily on the quality of the book, and for kids’ books how interesting and engaging it will likely be. Are the kids going to like or hate it and are they going to be strengthened or harmed by it? Again, these are educated guesses, because it’s adults, not kids themselves, that make up this reviewer community.

Lastly, we get to the people who adopt those books for their libraries. These would be public and school librarians, who, of course, read the reviews in making their decisions. They might also consult with parents about their choices; but they have to be, they must be, guided by their understanding of their whole community. In a school setting, that community is the whole enrollment in the school—all races, all genders, all religions.

In many schools, the teachers, who know their students, can make the choice to use a book within their lesson planning, or not. But their choices are limited, as I’ll spell out a little later.

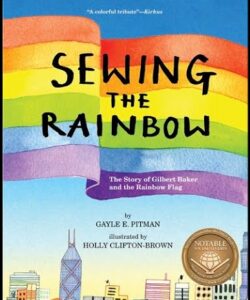

On May 3 of this year, the Spirit printed an article about the father of a first–grader in a local school. The parent voiced his objection in a school board online comment over a teacher reading the book “Sewing the Rainbow” aloud to the class. The book treats the backstory of how the LGBTQ “rainbow flag” came to be. The father described it in his written comment as a “complete disgusting betrayal of traditional family and military values.”

It’s that judgment call that shows the parent’s hand. He doesn’t like non–traditional families and doesn’t want his child to know about them. He’s putting into question not just this book, but the practice of the school to read books recommended by parents, as well as the list of recommended supplemental books the school maintains. “Sewing the Rainbow” was on that list.

I brought up this matter with Hali Taylor, director of the Shepherdstown Public Library, to get clear about the library’s position on the issue of challenging and banning a book. At the outset, Taylor said what she could say on the subject wouldn’t necessarily extend to what a public school policy would look like. For a public library, however, the broad guidelines are laid out by the American Library Association. The ALA grounds all of its policies to align with the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution as it concerns freedom of speech. Speech includes written, audio and video materials as well.

There are only two main issues that would disqualify a book from circulating, again following the ALA guidelines. These are pornography and works inciting violence. Hate speech, as such, is protected, as is writing that concerns sexual themes, as long as its purpose is not obscene. A person claiming that something is obscene or hateful isn’t good enough reason under the First Amendment to ban something. You have to make a claim that the material violates community standards.

Generally speaking, it’s the librarian to whom we entrust our interpretation of those community standards. Taylor said, “Literacy is our most important civil right. We can’t arbitrarily restrict someone’s right to read. Banning is counter to a free and open society.” Whether her approach statement applies as well to elementary school students is where the debate centers and the principle gets a little iffy because parents enter into the equation.

Do parents have the right to dictate what their children can read and not read? The answer, according to Taylor, is yes they do. But it’s not a right that they can demand a librarian to enforce. If a parent is concerned about their child finding something on a library shelf that they disapprove of, it is up to the parent to forbid it, not the librarian. The parent must do the enforcing, for instance, by going with the child to the library and overseeing and approving their choices. The librarian will not assume the parent’s role, no more than it will dictate what an adult user chooses to borrow. That also is library policy.

While libraries have an aversion to pulling books off their shelf that have made it through the rigorous publication and review process, most libraries have a process in place to “reconsider” some material at the request of a library user. The process in place at the Shepherdstown library involves filling out a form, which asks in specific detail what the user is objecting to. It can’t be a blanket statement, such as “it betrays traditional family values” or “it’s disgusting.” It may be something that personally doesn’t accord with the individual’s family values or beliefs, but that’s irrelevant information.

In addition, the form asks if the user has read the entire material and, if so, what harm it supposedly will cause to any and all who will use it. If they have not read, heard or viewed the whole work, the form asks them if they will do so before a formal review takes place and also if they will check out what unbiased reviewers have said about the material.

Finally, the form asks for suggestions about what to replace the material with. This last point also comes with an assurance that the library will make its suggested replacement available. For almost any book that is in print, one of the nine Eastern Panhandle libraries that participate in the Interlibrary Loan consortium can make it available if it’s in their collection. If not, the library will locate or purchase a copy.

So how often has it happened that the library consortium in the Panhandle has actually pulled something?

It’s rare enough that Taylor recalled only one incident. It was a how-to book concerned with ridding a garden of slugs. The reasoning was a little too gross to mention here. This book went through the full review process, but until a determination was made—by the library’s board of directors—it remained on the shelf.

School libraries are different from public libraries. Parents do have and should have more say into what schools do. It’s why we have Parent Teachers Associations. Note though that individual school districts are under the oversight of the state Board of Education, the government entity that prescribes the general outlines of the curriculum though the West Virginia College- and Career-Readiness Dispositions and Standards on a grade-by-grade basis.

It’s in the schools that most of the energy to restrict and ban books is taking place, across the nation and in West Virginia. Senate Bill 252, proposed in the latest state legislative session, set up strict guidelines to eliminate obscene matter in public schools. It specifically identified obscene materials as “indecent displays of a sexually explicit nature, [where] such prohibited displays shall include, but not be limited to, any transvestite and/or transgender exposure, performances or display to any minor.”

In the references to transvestite and transgender, it’s easy to see that this battle of the culture war is focused particularly on LGBTQ people. The intention is to stigmatize these people and to make children stop seeing them or, worse, to denigrate and abuse them. The bill as written makes no provisions for caring for these individuals if they’re harassed or harmed.

And, by the way, the book I started this article off with, “Sewing the Rainbow,” tells the story of Gilbert Baker, the individual who designed the iconic rainbow flag. The book, which has been banned elsewhere where the culture warriors operate, does not in the illustrated section identify Baker as gay. He’s just a kid who likes color and glitter, who doesn’t like war, and who’s happy with who he is. The kid grows up into an activist for LGBTQ causes.

So what’s wrong about that message? It’s a book that received the blessing of the American Psychological Association, which published it under its Magination Library reprint. It was also a finalist in the Children’s Choice Book Awards and a winner of the National Parenting Product Award in 2019. One person’s complaint can’t override all of that. It shouldn’t.

Here though Hali Taylor writes a much better conclusion: “Banning a book arbitrarily could mean that you are banning a point of view, banning scientific knowledge, banning someone’s experience of living in this world, banning opportunity for people who have limited resources, banning the opportunity to learn from others’ mistakes and successes.”

As a postscript, the American Library Association has designated Oct 1-7, 2023, as banned books week. The event carries on a 40-year tradition, but one which in the last two years has had to address a stunning increase in attempts to censor books. I hope it will be the loud and convincing counter we need to Let Freedom Read, this year’s theme.

Postscript

Gilbert Baker was a gay man and an activist for pro-LGBTQ and anti-war causes. When he joined the military after high school, his refusal to carry or fire a gun landed him in San Francisco as a conscientious-objector medic. In San Francisco he affiliated himself with the burgeoning gay rights political movement in that city. He was convinced that the movement needed a positive symbol to counter the negativity of the Nazi pink triangle, the only other widely recognized symbol associated with queer people. His personal sense of color and glitter, the universality of the rainbow as a positive icon, and his understanding of the power of flags to unite people all came together in his mind as a multicolored rainbow flag.

In retrospect it’s easy to understand from his biography how all of these influences resulted in the icon the world now associates with LGBTQ people. They were spurred by the choices Baker made in expressing himself personally. He was “genderqueer,” a term meaning that he would dress sometimes in male sometimes in female clothing, but more accurately in some clothing that transcended either a traditional male or female look. He performed in drag as both an entertainer and as an activist. He used drag to draw attention to the social and political causes he embraced.

It’s hard to look away from someone visibly challenging the norms. You pay attention. Drag is a form of expression protected by the 1st Amendment. It’s not obscene, any more than a whole cascade of male actors performing as women or female actors performing as men is obscene.

The causes Gilbert Baker believed in continue to be supported in his memory by the Gilbert Baker Foundation (GilbertBaker.com).

Similar Posts:

- None Found